The Communication Process

Communication is a process

by which information, message or thought is exchanged between individuals

through a common system of symbols, signs, signals, writing or behaviour.

The process needs:

- Two major participants: Sender or source and Receiver

- Two major communication tools: Message and Channel

- Four major communication functions and processes: Encoding, Decoding, Response and Feedback

- Hindrance: Noise

Nature

of communication

Sender or Source

In the communication process a person or organization that

has information to share to other person is a sender. A sender could be an

individual person like a salesperson or celebrity who talks about the product

or a non-personal entity like a corporation or organization.

The process of

communication starts as soon as the source select words, symbols, pictures,

etc. to present the message to receiver. The sender has to be careful while

selecting the communicator. He should know what knowledge the receiver has and

with whom it can relate itself to. This process is known as encoding. The

sender’s goal is to encode the message in such a way the receiver can decode it

easily. Few brands have already established its image through symbols.

Few examples in this regard could be Apple’s logo of an

apple’s silhouette with a bite taken out of it or the five coinciding circles

of Olympics.

Receiver

The receiver is a person, in the communication process, to

whom the sender shares his thoughts or message or information. They are

involved in the process of decoding. Decoding is the process of transforming the sender’s message back into

thought. The receiver is heavily influenced, to decode the message, by his

experiences or references, which give birth to the perceptions, attitudes and

values. It is very important in the process of communication that there should

be some common grounds between the two parties. The more the sender has the

information about the receiver, better he can put forth the message infront of

the receiver.

There are two major problems in the

communication process:

- No common ground between the sender and the receiver

- Age difference between the sender and the receiver

Another factor of age can lead to problems in establishing common ground

between senders and receivers. There are possibilities that when a young person

makes an advertisement for older customers it can have a youth bias in

advertising

Message

Message

The message is developed in the process of encoding. The

message can be verbal or nonverbal, oral or written, or symbolic. In advertising, the message may range from

simply writing some words or copy that will be read as a radio message to

producing an expensive television commercial. The products and brands acquire

meaning through the way they are advertised and consumers use products and

brands to express their social identities. These days to understand the

symbolic meaning that are communicated or advertised, the special focus is

given to semiotics. Semiotic is the study of the nature of the meaning and how

words, gestures, myths, signs, symbols, products/ services, theories acquire

meaning.

Every marketing message has three basic

components: an object, a sign or symbol and an interpretant. The object is the

product that is the focus of the message (e.g., Marlboro cigarettes). The sign

is the sensory imagery that represents the intended meanings of the object

(e.g., the Marlboro cowboy). The interpretant is the meaning derived (e.g.,

rugged, individualistic, American).

Every marketing message has three basic

components: an object, a sign or symbol and an interpretant. The object is the

product that is the focus of the message (e.g., Marlboro cigarettes). The sign

is the sensory imagery that represents the intended meanings of the object

(e.g., the Marlboro cowboy). The interpretant is the meaning derived (e.g.,

rugged, individualistic, American).

Marketers must consider the meanings consumers attach to the various signs and symbols. Semiotics may be helpful in analysing how various aspects of the marketing program—such as advertising messages, packaging, brand names, and even the nonverbal communications of salespeople (gestures, mode of dress)—are interpreted by receivers

Every marketing message has three basic

components: an object, a sign or symbol and an interpretant. The object is the

product that is the focus of the message (e.g., Marlboro cigarettes). The sign

is the sensory imagery that represents the intended meanings of the object

(e.g., the Marlboro cowboy). The interpretant is the meaning derived (e.g.,

rugged, individualistic, American).

Every marketing message has three basic

components: an object, a sign or symbol and an interpretant. The object is the

product that is the focus of the message (e.g., Marlboro cigarettes). The sign

is the sensory imagery that represents the intended meanings of the object

(e.g., the Marlboro cowboy). The interpretant is the meaning derived (e.g.,

rugged, individualistic, American).Marketers must consider the meanings consumers attach to the various signs and symbols. Semiotics may be helpful in analysing how various aspects of the marketing program—such as advertising messages, packaging, brand names, and even the nonverbal communications of salespeople (gestures, mode of dress)—are interpreted by receivers

Channel

The sender communicates

to the receiver through a medium. That medium is called a Channel. Channel of

communications are of two types: personal and non-personal.

Personal channels are direct interpersonal contact

with the receiver. For example salesman uses the personal channel to

communicate to the target individual or group. Other goods examples of personal

channel of communication are friends, co-workers, family members, etc. this

kind of communication could be identified as word of mouth.

The non-personal

communication occurs without the presences of interpersonal contact with the

potential consumers. It is directed to the mass through TV commercial broadcast

or print media. For example, on the television during the prime hour a

commercial of 30 seconds can communicate to millions of household at a time.

Print media includes newspapers, magazines, direct mail, and billboards;

broadcast media include radio and television.

The non-personal

communication occurs without the presences of interpersonal contact with the

potential consumers. It is directed to the mass through TV commercial broadcast

or print media. For example, on the television during the prime hour a

commercial of 30 seconds can communicate to millions of household at a time.

Print media includes newspapers, magazines, direct mail, and billboards;

broadcast media include radio and television.

Response/Feedback

The response is the result of the receiver reactions

after seeing, hearing, or reading the message. It could be non-observable actions

such as storing information in memory or immediate action such as dialling a

toll-free number to order a product advertised on television. It is very

essential for a marketer. The feedback can take different forms, closes the

loop in the communications flow and lets the sender monitor how the intended

message is being decoded and received. For example, in a personal-selling

situation, customers may pose questions, comments, or objections or indicate

their reactions through nonverbal responses such as gestures and frowns. The

salesperson has the advantage of receiving instant feedback through the

customer’s reactions. This method is used by Zara so as to be agile and

responsive in their processes.

This is not the case when mass media are used. As

advertisers are not in direct contact with the customers, therefore they use

other mediums to determine how their messages have been received through customer

inquiries, store visits, coupon redemption and reply cards. Research-based

feedback analyses readership and recall of ads, message comprehension, attitude

change, and other forms of response. With the information collected through feedback the advertiser can determine reasons for success or failure in the

communication process and modify accordingly.

Successful communication is accomplished when the marketer selects an

appropriate source, develops an effective message or appeal that is encoded

properly, and then selects the channels or media that will best reach the

target audience so that the message can be effectively decoded and delivered.

This is not the case when mass media are used. As

advertisers are not in direct contact with the customers, therefore they use

other mediums to determine how their messages have been received through customer

inquiries, store visits, coupon redemption and reply cards. Research-based

feedback analyses readership and recall of ads, message comprehension, attitude

change, and other forms of response. With the information collected through feedback the advertiser can determine reasons for success or failure in the

communication process and modify accordingly.

Successful communication is accomplished when the marketer selects an

appropriate source, develops an effective message or appeal that is encoded

properly, and then selects the channels or media that will best reach the

target audience so that the message can be effectively decoded and delivered. Noise

Any kind of distortion or interference, throughout the communication process, is noise. Errors or problems that occur in the encoding of the message, distortion in a radio or television signal, or distractions at the point of reception are examples of noise. When you are watching your favourite commercial on TV and a problem occurs in the signal transmission, it will obviously interfere with your reception, lessening the impact of the commercial. There may be other reasons as well for noises. May be the fields of experience of the sender and receiver don’t overlap. Lack of common ground may result in improper encoding of the message—using a sign, symbol, or words that are unfamiliar or have different meaning to the receiver.

Analyzing the Receiver

To make the communication effective, the marketers must know their target

audience. How do they perceive the company’s’ products or services, how should

the marketer communicate to influence their consumers’ decision making process

or how the market responds to various forms communication? Before they make

decisions regarding source, message, and channel variables, promotional

planners must understand the potential effects associated with each of these

factors. This section focuses on the receiver of the marketing communication.

It examines how the audience is identified and the process it may go through in

responding to a promotional message.

Identifying the Target Audience

Identifying the

audience is the starting point of the marketing communication process. After

identifying, the marketer can focus on advertising and promotion activities.

The target audience may consist of individuals, groups, niche markets, market

segments, or a general public or mass audience. To cater these groups the

approach will be different.

The target market may consist of individuals

who have specific needs and for whom the communication must be specifically

tailored. Mostly requires person-to person communication and is generally

accomplished through personal selling. A second level of audience aggregation

is represented by the group.

Marketers often must communicate with a group of people who make or influence

the purchase decision. Marketers look for customers who have similar needs and

wants and thus represent some type of market segment that can be reached with

the same basic communication strategy. Very small, well-defined groups of

customers are often referred to as market niches.

They can usually be reached through personal-selling efforts or highly targeted

media such as direct mail. The next level of audience aggregation is market segments, broader classes of

buyers who have similar needs and can be reached with similar messages. As

market segments get larger, marketers usually turn to broader-based media such

as newspapers, magazines, and TV to reach them.

Mass communication is a one-way flow of information from

the marketer to the consumer. Feedback on the audience’s reactions to the message

is generally indirect and difficult to measure. TV advertising will only allow

marketer to send the message but there is no guarantee that the information

will be attended to, processed, comprehended, or stored in memory for later

retrieval. Even if the advertising message is processed, it may not interest

consumers or may be misinterpreted by them. The marketer must enter the

communication situation with knowledge of the target audience and how it is

likely to react to the message. This means the receiver’s response process must

be understood, along with its implications for promotional planning and

strategy.

The Response Process

The Response Process

The most important aspect of developing effective communication programs

involves understanding the response process the receiver may go through in

moving toward a specific behavior (like purchasing a product) and how the

promotional efforts of the marketer influence consumer responses. In many

instances, the marketer’s only objective may be to create awareness of the company

or brand name, which may trigger interest in the product. In other situations,

the marketer may want to convey detailed information to change consumers’

knowledge of and attitudes toward the brand and ultimately change their

behavior.

Traditional Response Hierarchy Models

A number of models

have been developed to depict the stages a consumer may pass through in moving

from a state of not being aware of a company, product, or brand to actual

purchase behavior. The figure shows four of the best-known response hierarchy

models. While these response models may appear similar, they were developed for

different reasons.

The AIDA model was developed to

represent the stages a salesperson must take a customer through in the

personal-selling process. The salesperson must first get the customer’s

attention and then arouse some interest in the company’s product or service.

Strong levels of interest should create desire to own or use the product and

finally the action taken by the customer to buy the product or service.

The hierarchy of effects model shows

the process by which advertising works; it assumes a consumer passes through a

series of steps in sequential order from initial awareness of a product or

service to actual purchase. A basic premise of this model is that advertising

effects occur over a period of time. Advertising communication may not lead to

immediate behavioural response or purchase; rather, a series of effects must

occur, with each step fulfilled before the consumer can move to the next stage

in the hierarchy.

The innovation adoption model

evolved from work on the diffusion of innovations. This model represents the stages a

consumer passes through in adopting a new product or service. The steps

preceding adoption are awareness, interest, evaluation, and trial.

The information processing model

of advertising effects assumes the receiver in a persuasive communication

situation like advertising is an information processor or problem solver. The

stages of this model are similar to the hierarchy of effects sequence;

attention and comprehension are similar to awareness and knowledge, and

yielding is synonymous with liking. In this model there is one more stage

called retention. Retention stage is important since most promotional campaigns

are designed to provide information to the customers to use later when making a

purchase decision.

Each stage of the response hierarchy is a dependent variable that must be

attained and that may serve as an objective of the communication process. Each

stage can be measured, providing the advertiser with feedback regarding the

effectiveness of various strategies designed to move the consumer to purchase.

The information processing model may be an effective framework for planning and

evaluating the effects of a promotional campaign.

The hierarchy models of communication response are

useful to promotional planners from several perspectives.- They delineate the series of steps potential purchasers must be taken through to move them from unawareness of a product or service to readiness to purchase it.

- Potential buyers may be at different stages in the hierarchy, so the advertiser will face different sets of communication problems.

- The hierarchy models can also be useful as intermediate measures of communication effectiveness.

Alternative Response Hierarchies

Michael Ray has developed a model of information processing that

identifies three alternative orderings of the three stages based on perceived

product differentiation and product involvement. These alternative response

hierarchies are the standard learning, dissonance/attribution, and

low-involvement models.

In many purchase

situations, the consumer will go through the response process in the sequence

depicted by the traditional communication models. Ray terms this a standard

learning model, which consists of a learn → feel → do sequence. Information and knowledge acquired or

learned about the various brands are the basis for developing affect, or

feelings, that guide what the consumer will do (e.g., actual trial or

purchase). In this hierarchy, the consumer is viewed as an active participant

in the communication process who gathers information through active learning.

The

Dissonance/Attribution Hierarchy

This response hierarchy proposed by Ray involves

situations where consumers first behave, then develop attitudes or feelings as

a result of that behaviour, and then learn or process information that supports

the behaviour. This dissonance/attribution model, or do → feel → learn, occurs in situations where consumers must

choose between two alternatives that are similar in quality but are complex and

may have hidden or unknown attributes.

This response hierarchy proposed by Ray involves

situations where consumers first behave, then develop attitudes or feelings as

a result of that behaviour, and then learn or process information that supports

the behaviour. This dissonance/attribution model, or do → feel → learn, occurs in situations where consumers must

choose between two alternatives that are similar in quality but are complex and

may have hidden or unknown attributes.The consumer may purchase the product on the basis of a recommendation by some non-media source and then attempt to support the decision by developing a positive attitude toward the brand and perhaps even developing negative feelings toward the rejected alternative.

The Low-Involvement

Hierarchy

In this model the receiver

is viewed as passing from cognition to behavior to attitude change. This learn

→ do → feel

sequence is thought to characterize situations of low consumer involvement in

the purchase process. Ray suggests this hierarchy tends to occur when

involvement in the purchase decision is low, there are minimal differences

among brand alternatives, and mass-media (especially broadcast) advertising is

important.

In this model the receiver

is viewed as passing from cognition to behavior to attitude change. This learn

→ do → feel

sequence is thought to characterize situations of low consumer involvement in

the purchase process. Ray suggests this hierarchy tends to occur when

involvement in the purchase decision is low, there are minimal differences

among brand alternatives, and mass-media (especially broadcast) advertising is

important.

Understanding Involvement

It is important for the marketer to view involvement

as a variable that could help in explaining how consumers process advertising

information and how this information might affect message recipients. One

problem that usually occurs in this study of involvement is how to define and

measure it. Advertising managers must be able to determine targeted consumers’

involvement levels with their products.The FCB Planning Model

An interesting approach to analysing the communication situation comes from the work of Richard Vaughn of the Foote, Cone & Belding advertising agency. They developed an advertising planning model by building on traditional response theories such as the hierarchy of effects model and its variants and research on high and low involvement. They added the dimension of thinking versus feeling processing at each involvement level by bringing in theories regarding brain specialization. The right/left brain theory suggests the left side of the brain is more capable of rational, cognitive thinking, while the right side is more visual and emotional and engages more in the affective (feeling) functions. Their model, which became known as the FCB grid, delineates four primary advertising planning strategies—informative, affective, habit formation, and satisfaction—along with the most appropriate variant of the alternative response hierarchies.

The FCB grid provides a useful way for those involved in the advertising planning process, such as creative specialists, to analyse consumer–product relationships and develop appropriate promotional strategies. Consumer research can be used to determine how consumers perceive products or brands on the involvement and thinking/feeling dimensions. This information can then be used to develop effective creative options such as using rational versus emotional appeals, increasing involvement levels, or even getting consumers to evaluate a think-type product on the basis of feelings.

Cognitive Processing of Communications

The Cognitive Response

Approach

One of the most widely used

methods for examining consumers’ cognitive processing of advertising messages

is assessment of their cognitive responses, the thoughts that occur to them

while reading, viewing, and/or hearing a communication. These thoughts are

generally measured by having consumers write down or verbally report their

reactions to a message. The cognitive response approach has been widely used in

research by both academicians and advertising practitioners. Its focus has been

to determine the types of responses evoked by an advertising message and how

these responses relate to attitudes toward the ad, brand attitudes, and

purchase intentions.

One of the most widely used

methods for examining consumers’ cognitive processing of advertising messages

is assessment of their cognitive responses, the thoughts that occur to them

while reading, viewing, and/or hearing a communication. These thoughts are

generally measured by having consumers write down or verbally report their

reactions to a message. The cognitive response approach has been widely used in

research by both academicians and advertising practitioners. Its focus has been

to determine the types of responses evoked by an advertising message and how

these responses relate to attitudes toward the ad, brand attitudes, and

purchase intentions.

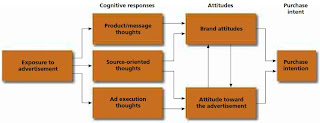

The below model depicts the

three basic categories of cognitive responses researchers have

identified—product/message, source oriented, and ad execution thoughts—and how

they may relate to attitudes and intentions.

The Elaboration Likelihood Model and Its Implications

Differences in the ways consumers’ process and respond

to persuasive messages are addressed in the elaboration likelihood model (ELM)

of persuasion. According to this model, the attitude formation or change

process depends on the amount and nature of elaboration, or processing, of

relevant information that occurs in response to a persuasive message. The ELM

shows that elaboration likelihood is a function of two elements, motivation and

ability to process the message. Motivation to process the message depends on

such factors as involvement, personal relevance, and individuals’ needs and

arousal levels. Ability depends on the individual’s knowledge, intellectual

capacity, and opportunity to process the message. For example, an individual

viewing a humorous commercial or one containing an attractive model may be

distracted from processing the information about the product.The elaboration likelihood model has important implications for marketing communications, particularly with respect to involvement. For example, if the involvement level of consumers in the target audience is high, an ad or sales presentation should contain strong arguments that are difficult for the message recipient to refute or counter-argue. If the involvement level of the target audience is low, peripheral cues may be more important than detailed message arguments. An interesting test of the ELM showed that the effectiveness of a celebrity endorser in an ad depends on the receiver’s involvement level. When involvement was low, a celebrity endorser had a significant effect on attitudes.

No comments:

Post a Comment